I am a Counselor at Law. I have been for more than 37 years, although I’m not sure how valuable my counsel would have been then. Today, most of the questions I’m asked center around divorce.

-My wife/husband wants a divorce. -How long will this take?

-How much will it cost?

-I want full custody of my kids.

-Will I lose the house if I move out?

-She/he had an affair!

-I had no idea!

I hear these comments hundreds of times a year. And then I’m asked, “So, what happens now? How does this work?” The answer is perhaps not what you expected, and it sounds like this: “Not the way you think; kind of like you think; and, it depends on what you’re trying to do.” Here’s what I mean.

Last things first. What are you trying to do? A divorce is an “official” determination that two people aren’t married any more. That’s an element of every divorce. It’s the minimum definition. The determination takes the form of a court order, which is required to talk about certain subjects, which I’ll get to in a moment.

The question of what you’re trying to do is directed toward how that order affects your life after you’re divorced: For example: Do you have kids? Who do they live with? How often? Who supports them? How? When do they see his family? When do they see hers? How do they experience Christmas/ Hanukkah/Kwanza/Easter/Passover/Thanksgiving/Halloween/July 4th/and other significant times? What happens if their parents start a new relationship? Or two? Will their parents divorce them, too?

That court order I mentioned can address all those questions, or very few of them. It might incorporate a 15-page Parenting Plan that discusses all these things. It might have two paragraphs that says one of the parents has legal and physical custody of the children, and the other parent will pay the custodian $1500 every month. And the parents will alternate having the children on major holidays. And that’s it.

A divorce is ‘kind of like you think,’ in the sense that a judge has to sign that order, even if the couple doesn’t agree on what should be in it. Maybe they never agree. Maybe they come to an agreement eventually. If they never agree, a judge will tell them how it’s going to be. Period. Does someone win while someone loses? Often, both of them feel as if they’ve lost.

How is it ‘not like you think?’ People are often surprised to learn the judge who signs the decree doesn’t have to make all the decisions. In fact, the only decision the judge really has to make is whether to sign the document a couple says they want as their decree. It’s true! Before that decision is made, the judge will need to be satisfied that the document includes everything it should–all those ‘certain subjects’ I referred to. But it’s much less work for a judge to agree with a couple’s decisions than it is to make the decisions for them.

Every couple who gets a divorce in Minnesota has the absolute right to make their own decisions about those ‘certain subjects.’ I can repeat that, or you can read that last sentence over again. And one couple’s decisions may not look like any other couple’s in the history of the state. Which is okay.

I am asked, “Well, what does the law say?” I answer as best I can, but often the question results from a misunderstanding of the law’s role. That role is not so much “You MUST do this,” and closer to “If you can’t work it out, this is what’ll happen.” Think of the written law as a safety net that keeps one spouse from taking serious advantage of the other.

What it means is, if a couple can reach their own agreement on those ‘certain subjects,’ the court will usually honor that agreement. Yes, there are conditions. You can’t agree to something that violates public policy. An example: a couple can’t agree that neither parent will ever pay child support to the other. Why? Lots of reasons, mostly having to do with reimbursing the government if you need government assistance. What you CAN agree to is what’s called a “reservation” of child support. When the court reserves support, it means no money changes hands. Usually, I see that in families where both parents earn enough to support their children independently of the other parent’s financial assistance. Another condition: the court would like to know the couple got some legal advice, and legal representation is better.

The ‘certain subjects’ include the marriage, real property, personal property, children, support of the family, which includes the children and either parent, financial assets, and debts. But divorce decrees can include conversations that disclose why the couple reached the agreements they did, and how those met the goals they have for their family, now and in the future. Those decrees may read much less like a fight and more like a strategic planning document.

How do you create that kind of divorce decree? It helps if you can bring a little different perspective to the task, what some lawyers call a “paradigm shift.”

The original paradigm, the impression we had when we left law school, was that a divorce was first and foremost a legal dispute, like any other. Sure, it had overtones of emotion and psychology and money and relationship, but if we could get the legalities straight, we’d be doing our job. Decades and cases later, many of us have realized that a divorce is more accurately described as an emotional, psychological, financial, and relational matter that has some legal overtones. We realized that by shifting the model of what we were doing, focusing on the realities and not the theories of the matter, our clients and their families got results that fit better, lasted longer, and let them experience the benefit of their family structure, which changed, but didn’t disappear.

Not everyone is independent enough to do this. Some folks have been so hurt before and during their marriage, that their own pain is all they can see. Working with someone they hold responsible is an impossibility. For couples–people–who need someone to decide, the judge can and will make those decisions.

It would be a different and arguably a better world if a divorcing couple had resolved their personal issues before starting their divorce, but it only rarely happens. But for couples who have enough insight to know divorce is not a substitute for therapy, control of the divorce outcome can be very much in their hands.

Next time, I’ll discuss how couples can get the information and the perspective they need to make those often complicated decisions. Spoiler alert: it takes a village–or a team.

-How long will this take?

-How much will it cost?

-I want full custody of my kids.

-Will I lose the house if I move out?

-She/he had an affair!

-I had no idea!

I hear these comments hundreds of times a year. And then I’m asked, “So, what happens now? How does this work?” The answer is perhaps not what you expected, and it sounds like this: “Not the way you think; kind of like you think; and, it depends on what you’re trying to do.” Here’s what I mean.

Last things first. What are you trying to do? A divorce is an “official” determination that two people aren’t married any more. That’s an element of every divorce. It’s the minimum definition. The determination takes the form of a court order, which is required to talk about certain subjects, which I’ll get to in a moment.

The question of what you’re trying to do is directed toward how that order affects your life after you’re divorced: For example: Do you have kids? Who do they live with? How often? Who supports them? How? When do they see his family? When do they see hers? How do they experience Christmas/ Hanukkah/Kwanza/Easter/Passover/Thanksgiving/Halloween/July 4th/and other significant times? What happens if their parents start a new relationship? Or two? Will their parents divorce them, too?

That court order I mentioned can address all those questions, or very few of them. It might incorporate a 15-page Parenting Plan that discusses all these things. It might have two paragraphs that says one of the parents has legal and physical custody of the children, and the other parent will pay the custodian $1500 every month. And the parents will alternate having the children on major holidays. And that’s it.

A divorce is ‘kind of like you think,’ in the sense that a judge has to sign that order, even if the couple doesn’t agree on what should be in it. Maybe they never agree. Maybe they come to an agreement eventually. If they never agree, a judge will tell them how it’s going to be. Period. Does someone win while someone loses? Often, both of them feel as if they’ve lost.

How is it ‘not like you think?’ People are often surprised to learn the judge who signs the decree doesn’t have to make all the decisions. In fact, the only decision the judge really has to make is whether to sign the document a couple says they want as their decree. It’s true! Before that decision is made, the judge will need to be satisfied that the document includes everything it should–all those ‘certain subjects’ I referred to. But it’s much less work for a judge to agree with a couple’s decisions than it is to make the decisions for them.

Every couple who gets a divorce in Minnesota has the absolute right to make their own decisions about those ‘certain subjects.’ I can repeat that, or you can read that last sentence over again. And one couple’s decisions may not look like any other couple’s in the history of the state. Which is okay.

I am asked, “Well, what does the law say?” I answer as best I can, but often the question results from a misunderstanding of the law’s role. That role is not so much “You MUST do this,” and closer to “If you can’t work it out, this is what’ll happen.” Think of the written law as a safety net that keeps one spouse from taking serious advantage of the other.

What it means is, if a couple can reach their own agreement on those ‘certain subjects,’ the court will usually honor that agreement. Yes, there are conditions. You can’t agree to something that violates public policy. An example: a couple can’t agree that neither parent will ever pay child support to the other. Why? Lots of reasons, mostly having to do with reimbursing the government if you need government assistance. What you CAN agree to is what’s called a “reservation” of child support. When the court reserves support, it means no money changes hands. Usually, I see that in families where both parents earn enough to support their children independently of the other parent’s financial assistance. Another condition: the court would like to know the couple got some legal advice, and legal representation is better.

The ‘certain subjects’ include the marriage, real property, personal property, children, support of the family, which includes the children and either parent, financial assets, and debts. But divorce decrees can include conversations that disclose why the couple reached the agreements they did, and how those met the goals they have for their family, now and in the future. Those decrees may read much less like a fight and more like a strategic planning document.

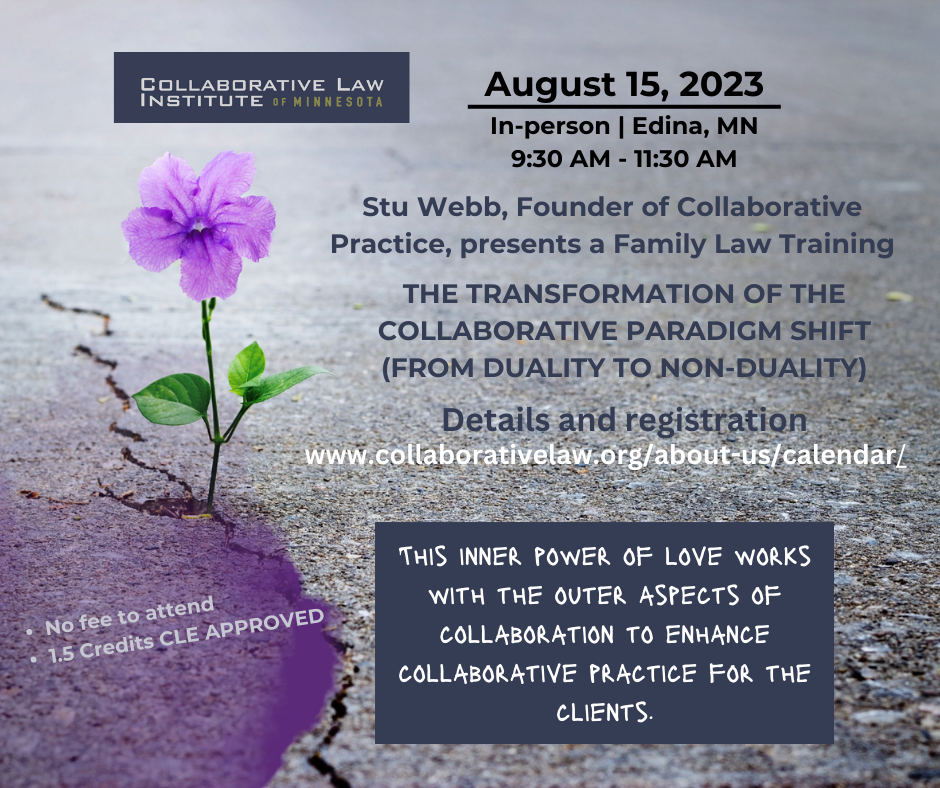

How do you create that kind of divorce decree? It helps if you can bring a little different perspective to the task, what some lawyers call a “paradigm shift.”

The original paradigm, the impression we had when we left law school, was that a divorce was first and foremost a legal dispute, like any other. Sure, it had overtones of emotion and psychology and money and relationship, but if we could get the legalities straight, we’d be doing our job. Decades and cases later, many of us have realized that a divorce is more accurately described as an emotional, psychological, financial, and relational matter that has some legal overtones. We realized that by shifting the model of what we were doing, focusing on the realities and not the theories of the matter, our clients and their families got results that fit better, lasted longer, and let them experience the benefit of their family structure, which changed, but didn’t disappear.

Not everyone is independent enough to do this. Some folks have been so hurt before and during their marriage, that their own pain is all they can see. Working with someone they hold responsible is an impossibility. For couples–people–who need someone to decide, the judge can and will make those decisions.

It would be a different and arguably a better world if a divorcing couple had resolved their personal issues before starting their divorce, but it only rarely happens. But for couples who have enough insight to know divorce is not a substitute for therapy, control of the divorce outcome can be very much in their hands.

Next time, I’ll discuss how couples can get the information and the perspective they need to make those often complicated decisions. Spoiler alert: it takes a village–or a team.

-How long will this take?

-How much will it cost?

-I want full custody of my kids.

-Will I lose the house if I move out?

-She/he had an affair!

-I had no idea!

I hear these comments hundreds of times a year. And then I’m asked, “So, what happens now? How does this work?” The answer is perhaps not what you expected, and it sounds like this: “Not the way you think; kind of like you think; and, it depends on what you’re trying to do.” Here’s what I mean.

Last things first. What are you trying to do? A divorce is an “official” determination that two people aren’t married any more. That’s an element of every divorce. It’s the minimum definition. The determination takes the form of a court order, which is required to talk about certain subjects, which I’ll get to in a moment.

The question of what you’re trying to do is directed toward how that order affects your life after you’re divorced: For example: Do you have kids? Who do they live with? How often? Who supports them? How? When do they see his family? When do they see hers? How do they experience Christmas/ Hanukkah/Kwanza/Easter/Passover/Thanksgiving/Halloween/July 4th/and other significant times? What happens if their parents start a new relationship? Or two? Will their parents divorce them, too?

That court order I mentioned can address all those questions, or very few of them. It might incorporate a 15-page Parenting Plan that discusses all these things. It might have two paragraphs that says one of the parents has legal and physical custody of the children, and the other parent will pay the custodian $1500 every month. And the parents will alternate having the children on major holidays. And that’s it.

A divorce is ‘kind of like you think,’ in the sense that a judge has to sign that order, even if the couple doesn’t agree on what should be in it. Maybe they never agree. Maybe they come to an agreement eventually. If they never agree, a judge will tell them how it’s going to be. Period. Does someone win while someone loses? Often, both of them feel as if they’ve lost.

How is it ‘not like you think?’ People are often surprised to learn the judge who signs the decree doesn’t have to make all the decisions. In fact, the only decision the judge really has to make is whether to sign the document a couple says they want as their decree. It’s true! Before that decision is made, the judge will need to be satisfied that the document includes everything it should–all those ‘certain subjects’ I referred to. But it’s much less work for a judge to agree with a couple’s decisions than it is to make the decisions for them.

Every couple who gets a divorce in Minnesota has the absolute right to make their own decisions about those ‘certain subjects.’ I can repeat that, or you can read that last sentence over again. And one couple’s decisions may not look like any other couple’s in the history of the state. Which is okay.

I am asked, “Well, what does the law say?” I answer as best I can, but often the question results from a misunderstanding of the law’s role. That role is not so much “You MUST do this,” and closer to “If you can’t work it out, this is what’ll happen.” Think of the written law as a safety net that keeps one spouse from taking serious advantage of the other.

What it means is, if a couple can reach their own agreement on those ‘certain subjects,’ the court will usually honor that agreement. Yes, there are conditions. You can’t agree to something that violates public policy. An example: a couple can’t agree that neither parent will ever pay child support to the other. Why? Lots of reasons, mostly having to do with reimbursing the government if you need government assistance. What you CAN agree to is what’s called a “reservation” of child support. When the court reserves support, it means no money changes hands. Usually, I see that in families where both parents earn enough to support their children independently of the other parent’s financial assistance. Another condition: the court would like to know the couple got some legal advice, and legal representation is better.

The ‘certain subjects’ include the marriage, real property, personal property, children, support of the family, which includes the children and either parent, financial assets, and debts. But divorce decrees can include conversations that disclose why the couple reached the agreements they did, and how those met the goals they have for their family, now and in the future. Those decrees may read much less like a fight and more like a strategic planning document.

How do you create that kind of divorce decree? It helps if you can bring a little different perspective to the task, what some lawyers call a “paradigm shift.”

The original paradigm, the impression we had when we left law school, was that a divorce was first and foremost a legal dispute, like any other. Sure, it had overtones of emotion and psychology and money and relationship, but if we could get the legalities straight, we’d be doing our job. Decades and cases later, many of us have realized that a divorce is more accurately described as an emotional, psychological, financial, and relational matter that has some legal overtones. We realized that by shifting the model of what we were doing, focusing on the realities and not the theories of the matter, our clients and their families got results that fit better, lasted longer, and let them experience the benefit of their family structure, which changed, but didn’t disappear.

Not everyone is independent enough to do this. Some folks have been so hurt before and during their marriage, that their own pain is all they can see. Working with someone they hold responsible is an impossibility. For couples–people–who need someone to decide, the judge can and will make those decisions.

It would be a different and arguably a better world if a divorcing couple had resolved their personal issues before starting their divorce, but it only rarely happens. But for couples who have enough insight to know divorce is not a substitute for therapy, control of the divorce outcome can be very much in their hands.

Next time, I’ll discuss how couples can get the information and the perspective they need to make those often complicated decisions. Spoiler alert: it takes a village–or a team.

-How long will this take?

-How much will it cost?

-I want full custody of my kids.

-Will I lose the house if I move out?

-She/he had an affair!

-I had no idea!

I hear these comments hundreds of times a year. And then I’m asked, “So, what happens now? How does this work?” The answer is perhaps not what you expected, and it sounds like this: “Not the way you think; kind of like you think; and, it depends on what you’re trying to do.” Here’s what I mean.

Last things first. What are you trying to do? A divorce is an “official” determination that two people aren’t married any more. That’s an element of every divorce. It’s the minimum definition. The determination takes the form of a court order, which is required to talk about certain subjects, which I’ll get to in a moment.

The question of what you’re trying to do is directed toward how that order affects your life after you’re divorced: For example: Do you have kids? Who do they live with? How often? Who supports them? How? When do they see his family? When do they see hers? How do they experience Christmas/ Hanukkah/Kwanza/Easter/Passover/Thanksgiving/Halloween/July 4th/and other significant times? What happens if their parents start a new relationship? Or two? Will their parents divorce them, too?

That court order I mentioned can address all those questions, or very few of them. It might incorporate a 15-page Parenting Plan that discusses all these things. It might have two paragraphs that says one of the parents has legal and physical custody of the children, and the other parent will pay the custodian $1500 every month. And the parents will alternate having the children on major holidays. And that’s it.

A divorce is ‘kind of like you think,’ in the sense that a judge has to sign that order, even if the couple doesn’t agree on what should be in it. Maybe they never agree. Maybe they come to an agreement eventually. If they never agree, a judge will tell them how it’s going to be. Period. Does someone win while someone loses? Often, both of them feel as if they’ve lost.

How is it ‘not like you think?’ People are often surprised to learn the judge who signs the decree doesn’t have to make all the decisions. In fact, the only decision the judge really has to make is whether to sign the document a couple says they want as their decree. It’s true! Before that decision is made, the judge will need to be satisfied that the document includes everything it should–all those ‘certain subjects’ I referred to. But it’s much less work for a judge to agree with a couple’s decisions than it is to make the decisions for them.

Every couple who gets a divorce in Minnesota has the absolute right to make their own decisions about those ‘certain subjects.’ I can repeat that, or you can read that last sentence over again. And one couple’s decisions may not look like any other couple’s in the history of the state. Which is okay.

I am asked, “Well, what does the law say?” I answer as best I can, but often the question results from a misunderstanding of the law’s role. That role is not so much “You MUST do this,” and closer to “If you can’t work it out, this is what’ll happen.” Think of the written law as a safety net that keeps one spouse from taking serious advantage of the other.

What it means is, if a couple can reach their own agreement on those ‘certain subjects,’ the court will usually honor that agreement. Yes, there are conditions. You can’t agree to something that violates public policy. An example: a couple can’t agree that neither parent will ever pay child support to the other. Why? Lots of reasons, mostly having to do with reimbursing the government if you need government assistance. What you CAN agree to is what’s called a “reservation” of child support. When the court reserves support, it means no money changes hands. Usually, I see that in families where both parents earn enough to support their children independently of the other parent’s financial assistance. Another condition: the court would like to know the couple got some legal advice, and legal representation is better.

The ‘certain subjects’ include the marriage, real property, personal property, children, support of the family, which includes the children and either parent, financial assets, and debts. But divorce decrees can include conversations that disclose why the couple reached the agreements they did, and how those met the goals they have for their family, now and in the future. Those decrees may read much less like a fight and more like a strategic planning document.

How do you create that kind of divorce decree? It helps if you can bring a little different perspective to the task, what some lawyers call a “paradigm shift.”

The original paradigm, the impression we had when we left law school, was that a divorce was first and foremost a legal dispute, like any other. Sure, it had overtones of emotion and psychology and money and relationship, but if we could get the legalities straight, we’d be doing our job. Decades and cases later, many of us have realized that a divorce is more accurately described as an emotional, psychological, financial, and relational matter that has some legal overtones. We realized that by shifting the model of what we were doing, focusing on the realities and not the theories of the matter, our clients and their families got results that fit better, lasted longer, and let them experience the benefit of their family structure, which changed, but didn’t disappear.

Not everyone is independent enough to do this. Some folks have been so hurt before and during their marriage, that their own pain is all they can see. Working with someone they hold responsible is an impossibility. For couples–people–who need someone to decide, the judge can and will make those decisions.

It would be a different and arguably a better world if a divorcing couple had resolved their personal issues before starting their divorce, but it only rarely happens. But for couples who have enough insight to know divorce is not a substitute for therapy, control of the divorce outcome can be very much in their hands.

Next time, I’ll discuss how couples can get the information and the perspective they need to make those often complicated decisions. Spoiler alert: it takes a village–or a team.  Ask anyone who has ever gone through a divorce whether they have recommendations for how the process could have gone better and I bet they would have a list of ideas. They would likely identify a need for their legal counsel to have communicated more frequently with them and to have helped more to educate them about their options at each step of the process. They would likely say they worried that their legal counsel had a perverse incentive to provide more services (more hours of billable work) seemingly regardless of the effectiveness of those services because they billed by the hour and the client didn’t see or understand much of the work that the attorney was doing.

Many professions, including law and medicine, are rethinking the most basic aspects of the services they provide and how they provide them and are defining new ways of doing things.

I was reminded of this when reading an article in the New York Times titled When Medicine is Futile, which addressed the issue of whether medical providers are sometimes (or even as a matter of standard office policy) over-treating patients during end-of-life medical care.

The article brought up the issue of whether medical providers—in the name of patient protection and patient care—may actually be working against the patient’s best interests (even affirmatively harming patients) by administering an inappropriately excessive—and futile—list of medical interventions.

The article references a new report by the Institute of Medicine titled Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life (2014). Some of the recommendations for improved care include increased provider-patient communication, education of medical providers in alternatives such as palliative care, increased patient planning and decision making, and different payment structures that may better align with patient care quality more than just the quantity of the services provided. The gist of the recommendations to improve patient care relate mostly to increased communication, increased education of providers and patients about alternative options, and creating systemic incentives to reward quality patient care over simply providing a high quantity of billable services.

Similar to a hospital emergency room, courtrooms offer intensive and expensive services. In the court system, attorneys rack up immense billable hours based on providing clients with a large quantity of paperwork to submit to the court. In the courtroom, attorney-client communication, client education about their options for resolution and client power to make their own decisions can be lacking.

The legal system, like the medical system, is going through a paradigm shift where legal service providers are rethinking even the most basic aspects of the services they provide and how they provide them and are finding new ways of doing things.

Collaborative Practice providers implement best practices similar to those recommended for the medical profession referenced in the report mentioned above, only in the area of legal representation instead of medical care. In the Collaborative process, there is an increased focus on the quality, rather than just the quantity, of legal services. This change in focus is inherent in the agreement of the clients and attorneys that they will not go to court to resolve their conflict as part of the Collaborative process. In the Collaborative model, clients meet with a team of professionals to share information, learn about alternatives that might not have been considered, and evaluate their options in an open discussion. This provides clients with increased knowledge about their options, increased communication with professionals, and true decision-making authority.

Ask anyone who has ever gone through a divorce whether they have recommendations for how the process could have gone better and I bet they would have a list of ideas. They would likely identify a need for their legal counsel to have communicated more frequently with them and to have helped more to educate them about their options at each step of the process. They would likely say they worried that their legal counsel had a perverse incentive to provide more services (more hours of billable work) seemingly regardless of the effectiveness of those services because they billed by the hour and the client didn’t see or understand much of the work that the attorney was doing.

Many professions, including law and medicine, are rethinking the most basic aspects of the services they provide and how they provide them and are defining new ways of doing things.

I was reminded of this when reading an article in the New York Times titled When Medicine is Futile, which addressed the issue of whether medical providers are sometimes (or even as a matter of standard office policy) over-treating patients during end-of-life medical care.

The article brought up the issue of whether medical providers—in the name of patient protection and patient care—may actually be working against the patient’s best interests (even affirmatively harming patients) by administering an inappropriately excessive—and futile—list of medical interventions.

The article references a new report by the Institute of Medicine titled Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life (2014). Some of the recommendations for improved care include increased provider-patient communication, education of medical providers in alternatives such as palliative care, increased patient planning and decision making, and different payment structures that may better align with patient care quality more than just the quantity of the services provided. The gist of the recommendations to improve patient care relate mostly to increased communication, increased education of providers and patients about alternative options, and creating systemic incentives to reward quality patient care over simply providing a high quantity of billable services.

Similar to a hospital emergency room, courtrooms offer intensive and expensive services. In the court system, attorneys rack up immense billable hours based on providing clients with a large quantity of paperwork to submit to the court. In the courtroom, attorney-client communication, client education about their options for resolution and client power to make their own decisions can be lacking.

The legal system, like the medical system, is going through a paradigm shift where legal service providers are rethinking even the most basic aspects of the services they provide and how they provide them and are finding new ways of doing things.

Collaborative Practice providers implement best practices similar to those recommended for the medical profession referenced in the report mentioned above, only in the area of legal representation instead of medical care. In the Collaborative process, there is an increased focus on the quality, rather than just the quantity, of legal services. This change in focus is inherent in the agreement of the clients and attorneys that they will not go to court to resolve their conflict as part of the Collaborative process. In the Collaborative model, clients meet with a team of professionals to share information, learn about alternatives that might not have been considered, and evaluate their options in an open discussion. This provides clients with increased knowledge about their options, increased communication with professionals, and true decision-making authority.