Last time I wrote about some of the realities of the divorce process and some of the different ways by which a final divorce decree can be created. It may have come as a surprise to learn that a couple has enormous legal autonomy to create their own decree, but it’s a fact.

Last time I wrote about some of the realities of the divorce process and some of the different ways by which a final divorce decree can be created. It may have come as a surprise to learn that a couple has enormous legal autonomy to create their own decree, but it’s a fact.

So how does a couple with limited knowledge of tax planning, deferred compensation, and employee stock options figure out what they have and what to do with it? Is it good for a two-year-old to be parented the same way his eight-year-old brother and 12-year-old sister are? Where do I find out? And how do I bring that information into the conversation without increasing the conflict?

In a word, the answer is, “Neutrals.” Financial neutral, neutral child specialist, neutral coach. Why neutral? Because a neutral works for both of you. If you’re fighting about financial issues, the odds are pretty high each spouse will want to hire their own expert to tell the judge what’s REALLY going on with the parties’ assets and debts. Would you be shocked to learn that two such financial experts with very similar training and experience can offer opinions that are many thousands of dollars apart? Would it surprise you to know that husband’s financial expert could care less whether wife can meet her monthly budget? Or whether wife’s expert cares that husband is going in the hole every month after paying guidelines child support? Would it make more sense to handle the children’s expenses so that the family’s income covers as many of their needs as possible? Would you prefer to be able to choose whether your property division emphasizes cash, or retirement? Are you comfortable with risk, or do you need maximum security, and what combination of assets best achieves either goal?

And always, there’s the same question: If goal X is crucial to achieve, what are you willing to give up in order to get it?

How about parenting? Do you “want the kids 50/50?” What would that look like? Are their parents driving them between homes every day? What’s that feel like to those children? To your 12-year-old? To her two-year-old sister? Is it okay for them both to sleep in your home for five nights straight? Why or why not? Is there an impact on the youngest if she does? Is their other parent only a parent 50% of the time? Are you? Do you envy their relationship with their other parent? Does it show? Or do they know you are genuinely happy that they had a good weekend/week/Christmas vacation with Mom/Dad? Do any of these questions really matter?

Short answer: Yes, they’re at the heart of your divorce.

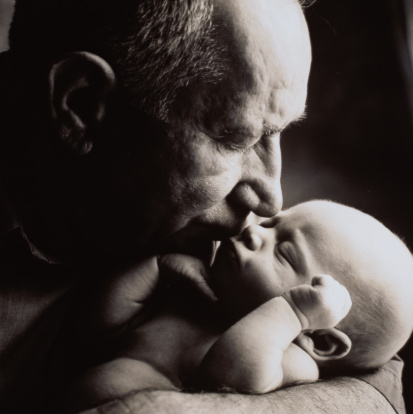

Although you changed the diapers, nursed, fed, bathed, dressed, played, vacationed, listened, lectured, or just . . . beheld, you may not know everything you need–or want–to. How does the mind develop? What is a child’s sense of the world? How do they see others? Or you? And when does that start? When does it change? When do they conceive of themselves as “other?” What gives them comfort? Makes them feel safe? Are those the same things that reassure their parents? What makes them anxious? Should you find these things out? Can you make up for lost time or hurtful words? Can they forgive you? Can you forgive yourself? Most importantly, can your lawyer give you the best answer to these questions?

Or would you rather learn them from a child psychologist with decades of experience? A neutral child psychologist. Someone whose role is to be the voice of your children, a conduit from their heart to yours. An information source whose information comes directly from your kids, with their permission. A safe person for them to tell.

[Intermission]

Can you talk to the person you married? You know–that someone that you used to love. Can they hear you when you do?

That’s why you need a neutral coach.

If you and your spouse decide to divorce in a Collaborative process where you have to make the decisions, where you have to talk to each other, don’t you need to be heard? Even if you’re not in a Collaborative process, 95 percent of the cases settle without a trial. In most of those, lawyers discourage clients from direct communication with their spouse. In fairness to my colleagues, that’s usually because the clients don’t know how to do it constructively. They’re hurt. They’re pissed. They want to be real clear on that point to anyone within earshot.

But if you approach the divorce process as a problem-solving exercise, are you going to let your “mouthpiece” tell your spouse about your priorities? Will it mean as much, will it be as believable, as if you say it yourself? If you’re going to acknowledge their good parenting, aren’t you the only one who can say it?

If you have to revise your concept of what would be “fair,” would you like to be able to hold on to as much of it as possible? Or will you blow up, throw the baby out with the bath water? A coach can help you find the words, and the room in your heart to say them; can hand you the towel to dry the baby off.

Coaches constantly remind us that a “good divorce” is not a zero sum game. Yes, he had an affair! Yes, he failed to acknowledge you at every turn. Yes, she constantly criticized the way you did things, things she never would have attempted. Yes, “too much” was never “enough” for her. And, and, and . . . But, are you going to save for college? Can you send your daughter to language immersion camp? How do you talk to him about this shoplifting arrest? Can you count on her to take the kids if you’re called out of town on business? If the chemo knocks you out, will he be able to get them to school and their games? They cut his overtime; can you cover their lunches this month?

Think it won’t happen to you? Think this was settled in the Decree? Guess what? Life happens. My clients have asked all those questions of their Ex’s, and many others besides. How will you ask? How will you answer when you are asked? Coach. Coach. Coach.

Did I mention a Coach?

Four’s a crowd

So why all these people?

Simple: More bang for the buck!

What do I mean? Just this: When you have a job to do, who do you ask, someone who specializes in it, or someone who dabbles? If the dabbler costs twice as much, what then? You ask the best person qualified to do the job! You shouldn’t ask your lawyer to be your psychologist. You shouldn’t ask your therapist to be your lawyer (although it sure would be nice to find an experienced lawyer who charges $180 an hour, right?). For every hour your coach helps you find answers, you saved yourself $100 over having your lawyer do it, give or take. Put another way, if you expect your lawyer to help you find those answers, you will have overspent and perhaps gotten an inferior product into the bargain. Yes, this is the lawyer speaking.

Next time: The Power of Neutrality